If your research methods professor asserted that the Earth was flat, you and your classmates would likely give her some strange looks. When you compare that statement with what you know about the world, you immediately conclude that the statement is grossly inaccurate. It’s just plain wrong! The Earth is (nearly) round.

Let’s look at that question from a different perspective: How do you know that the Earth is round? This book is dedicated to a particular method of knowing, and explaining how social scientists know social facts. Before we dig deeper into what science is and how it is done, let’s look at some other methods of knowing things.

A common method of knowing something is by directly experiencing it. Most police officers, for example, can tell you with certainty that having pepper spray in your eyes is very uncomfortable. We can refer to these sorts of learning experiences as informal observations. This type of learning is important; we couldn’t get along in life without it. We should keep in mind, however, that such observations are prone to error because they are not systematic. Because these observations are not systematic, they have the potential to be biased because of our natural tendency to make selective observations.

Selective observations occur when we note particular instances that support a preconceived notion of how things work. In other words, we see what we want to see and disregard the rest. We also have a natural tendency to make generalizations prematurely and without enough information. Generalizations are rules about how the world (usually) works and are of great value. Overgeneralizations, however, are dangerous and result in a broad spectrum of social ills.

An overgeneralization is when a broad pattern is erroneously assumed to exist based on very limited observations.

Science is an effort to understand (or improve our understanding) of the world, with observable evidence as the basis of that understanding. This evidence can be gathered through the systematic observation of natural phenomena or through experimentation. The Social Sciences are academic disciplines that scientifically study human aspects of the world using the scientific method. Social scientists often take all of these scientific considerations into account using the phrase “research methods.”Another important method of knowing is the method of authority. In other words, we believe something to be true because some authority tells us so. It would be impossible to investigate everything on our own and make our own observations. We often defer to experts. Sometimes we defer to people who are not actually experts as if they were.

One of the most important things to keep in mind about social scientific knowledge creation is that social scientists aim to explain patterns in social groups. Most of the time, such a pattern will not explain every single person’s experience. This fact about the social sciences is at once intriguing and annoying. It is intriguing because, even though the individuals who create a pattern may not be the same over time and may not even know one another, together they create a pattern.

In historical and qualitative research, the focus on patterns may extend to understanding the context, mechanisms, or narratives that give rise to these patterns. Such research methods are particularly useful for exploring why and how these patterns form and evolve, often providing the rich detail and deeper understanding that is sometimes lacking in purely quantitative approaches. The patterns uncovered in historical and qualitative research might not be generalizable in the statistical sense, but they offer valuable insights into cultural, social, or historical processes that shape collective behavior.

Those new to social scientific thinking may find these patterns frustrating because they may believe that the patterns that describe their gender, their ethnicity, or some other facet of their lives don’t really represent their experience. That may well be an accurate observation. A pattern can exist among your group without your individual participation in it. Social scientists are pretty good at describing groups and predicting group behavior and pretty terrible at predicting what any individual will do. When scientists use the empirical approach to acquire knowledge, they are said to be conducting empirical research.

The most critical difference between our everyday observations and empirical research is that research is planned in advance of making the observation. This planning process helps the researcher greatly reduce the possibility of coming to wrong conclusions. Social scientists consider whom to observe, how to observe them, and when to observe them. A key word here is “systematically.” Conducting science (a.k.a. research) is a deliberate process! Unlike the other ways of knowing, science gathers information in a way that is structured and purposeful.

The Role of Theory

For most college students, the mere mention of the word theory brings on a sick feeling of dread, surpassed only by funerals and root canals. A theory, they suspect, is a useless intellectual abstraction, the opposite of a fact. Facts are real, tangible things. Theories are ephemeral things with little or no practical application or use. This unfortunate misconception tends to overshadow the fact that theory (when properly developed) is an incredibly useful tool for explaining the social world in which we live. Theory can help us make sense of things we observe in the world around us. In addition, the theory can be tested against new facts learned from observation. The essence of a theory is to explain how two or more phenomena are related to each other.

For a theory to be truly a scientific theory, the statements contained within the theory must deal with observable facts. That is, they must refer to actual events—things that scientists can observe and measure. They do not (indeed, cannot) answer questions about what ought to be or what should be. Such questions are better suited to philosophy and theology. That is not to say that these questions are unimportant, but it must be realized that science, by its very nature, is completely unequipped to deal with them. Social scientific theory does not deal in philosophical, religious, or metaphysical explanations of social phenomena.

From the above, we can gather that the two pillars of science are theory and observation. That is, we must have logical explanations as to how the social world works, and those explanations must be able to be falsified by making real-world observations. If either of these two elements is missing, then a particular effort to explain the social world is not science.

The Scientific Method

The scientific method is a group of techniques for investigating phenomena, discovering new knowledge, and improving on previous knowledge. The term phenomenon simply means something that happens that can be observed. As we learned above, the two pillars of the scientific method are theory and observation. To be truly scientific, those observations cannot be haphazard. Science requires that observations be made in an objective and systematic way. Often, objectivity in the social sciences is more difficult to achieve than in other scientific endeavors.

Two Roads to the Truth

Science seeks to explain, predict, and ultimately control social phenomena. The first stage in the development of any science is the ability to explain. When it comes to developing such explanations, the researcher can go by two distinct paths. Social scientific inquiry may take one of two basic forms: inductive or deductive. In inductive research, the goal of a research is to infer theoretical concepts and relationships from observed data. In deductive research, the goal of the researcher is to test concepts and patterns known from theory using new empirical data.

It is for this reason that inductive research is also called theory-building research, and deductive research is called theory-testing research. Often the goal of theory testing is not merely to test a theory, but perhaps to refine and extend it. These distinctions are important in research because they often dictate the research design that the researcher chooses, the analytic techniques that are appropriate, and the veracity of statements that can be made based on the research findings.

Given the “Two Roads to the Truth” framework that outlines inductive and deductive approaches in social scientific inquiry, one could attempt to generalize about the most common strategies for researchers in different fields:

History

Historical research often leans towards the inductive side, where researchers examine primary and secondary sources to build a narrative or theory about past events. It’s largely about understanding context, causality, and the interplay of different factors over time, often with the aim of theory-building based on empirical evidence.

Political Science

Political Science research can be both inductive and deductive. Quantitative political science, such as analyses using datasets of voting patterns or international relations, is often deductive and theory-testing in nature. Meanwhile, qualitative approaches like case studies or ethnographic research in political science are more inductive.

Criminal Justice

In criminal justice, both inductive and deductive methods are used. Data-driven approaches may study crime statistics to deduce patterns and test theories. Inductive reasoning might be used in qualitative studies exploring the experiences of individuals in the criminal justice system to build new theories.

Psychology

Psychology extensively uses both methods, although there might be a stronger emphasis on the deductive, theory-testing approach. Experimental designs, often used in psychology, are set up to test hypotheses derived from existing theories about human behavior.

Social Work

Social work is largely an applied field and may lean more towards inductive reasoning. Qualitative methods like interviews and observations are often used to understand individual and community needs, and theories may be built based on these empirical observations.

In summary, while there are general tendencies for each field, it’s important to note that most disciplines employ a mixture of both inductive and deductive methods, depending on the research question and the aims of the study. The choice between inductive and deductive research often guides the research design, analysis techniques, and the interpretations that can be made from the data.

The Probabilistic Nature of Social Science

Note that you will almost never see the idea of a scientific law in the social scientific literature. There may be laws of gravity, but there are no laws of human behavior. This is because human behaviors are essentially probabilistic. In other words, we can say what is likely to happen under a given set of circumstances, but we are never sure. Unfortunately, for the social scientist, human behavior is far too complex to develop universal laws to explain it.

The ultimate goal of many social science researchers is to alter human behavior. Criminology, for example, would be hollow if it did not inform us as to how crimes may be prevented. Educational theories would be useless if they did not inform us how to improve learning. Psychological theories would be pointless if they did not inform us how to improve the lives of people.

The essence of the social sciences (in an applied sense) is to help people. In practice, this is done not by the application of scientific laws but rather by shifting probabilities in a particular direction. That is, social scientific interventions make it more or less likely that a particular behavior will occur. Much of the time, the social scientist is trying to eliminate a particular dangerous, unhealthy, or destructive behavior. If we could rely on universal laws, then we could be successful in helping everyone all of the time. Social scientists often refer to their theoretical explanations as models because of this lack of universal application.

The idea of a model is a simplified version of an observable reality. You can make a model airplane, but it cannot be used to take you to London. When social scientists derive models of reality, the necessary complexity to explain the social world perfectly is lost. This simplification may seem ill-advised at first glance, but it is a necessary and prudent approach. To explain the full spectrum of human behavior would take thousands of pieces of information (variables in the language of science). To control human behavior, we would have to be able to manipulate those thousands of variables. Theories in physics and chemistry often deal with very small sets of variables, and this makes nearly perfect predictions of real-world outcomes possible. Engineers prove this all of the time; bridges do not often collapse.

Social scientists are forced to sift through thousands of potential influences on human behavior and attempt to describe the most important ones. From this set of important variables, the researcher must determine which ones can be manipulated within ethical and practical limits. If we link the concept of guardianship to crime, for example, we can reduce crime by increasing the level of guardianship in a particular environment. This, however, will not eliminate crime. Social scientists are in the business of making things better, but we do a terrible job of fixing them entirely.

Selecting Your Own Research Problem

Students often complain that coming up with a good idea for a research project is the hardest part of the process. It does not have to be. All you need to do is reflect back on the issues from your classes and readings in the social sciences to an issue that has interested you—something that you want to understand better or know more about. Once you have selected a broad topic of interest, you are well on your way. All you need to do after that is formulate a research question and then formulate that into a formal hypothesis.

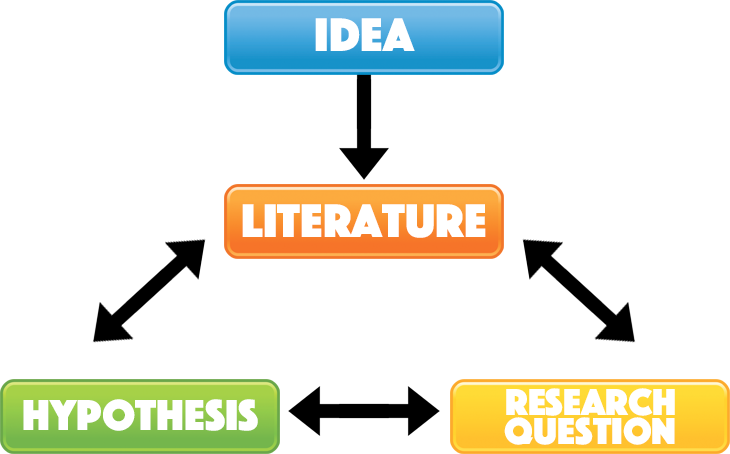

At this point, we break away from the traditional model of the research process that you will find in most research texts. The usual process goes something like this.

- Come up with an idea.

- Develop a research question from your idea.

- Develop a hypothesis from your research question (if this can be done).

- Conduct an exhaustive literature review.

That, in our opinion, is not the best approach. We view research as a cyclical process—each step forces you to go back to the preceding steps and rethink what you’ve done so far. We suggest the approach in the following figure:

What this model suggests is that you will use the literature to delve more deeply into your idea so that you can formulate a specific research question. Then you will further use the literature to refine your research question into a good research hypothesis.

What’s wrong with the more traditional model? It serves to artificially restrict your hypothesis to a version that is not as complete or accurate as it could be. Remember that a hypothesis is an educated guess. An important part of reviewing the literature is educating yourself about your topic. Let the findings of other researchers guide you in the process of narrowing your general idea down to a specific, testable hypothesis.

We are not baking cookies here; you cannot simply follow a series of numbered steps and expect quality research as a final product. You must constantly think of your research project as a highly mutable whole. Every time you do something, everything that came before that step is likely to need revision.

Things to Avoid

The selection of your research problem is extremely important for several reasons. The most important thing to remember is that if you select an “easy” topic that you have no interest in, you will be completely, utterly miserable before the project is finished.

Another thing to avoid is becoming overly attached to your idea. Remember, it is a research project, not your child. Just as children grow and change, so too must your research project. Even if you’ve spent a huge amount of time and energy going down the wrong path, remember that the process is cyclical and that you are getting ever closer to where you want to be—unless you stick to bad ideas because you just can’t move on.

When taking a multiple-choice test, your first instinct is usually the best choice. When selecting a research problem, there is no such recommendation. Your first idea may be a bad one for any of several reasons. There may not be enough literature on the topic for you to conduct an adequate literature review, or there may be such a wealth of literature that you are beating a dead horse.

Beating a dead horse doesn’t do anything for science. If something is well established, then there is no use doing the same research again. Do not, however, confuse beating a dead horse with valid replication studies. Replication is a key element of science. Usually, replicated studies will fill in blanks in the knowledge about your topic—you are asking the same questions that a previous researcher asked, but you are usually attempting to make some improvement.

Where to Get Ideas

In rare cases, a student knows what research questions they want to ask. This rare breed can skip ahead. For the rest of us, we need to look no further than our own past. Personal experience can be a fruitful starting point. Your personal reading can be a good starting point as well. If you are reading a book or article and get angry because an obvious question is not answered, then you have stumbled on a potentially great research idea. Another great way to get research ideas is to ask a professional researcher for suggestions. Academics are constantly reading the professional literature and constantly coming up with brilliant research ideas that they will one day pursue. Your research professor may well give you one of her little gems to see what you can do with it.

Idea versus Research Question

This is a good point to clarify the difference between an idea and a research question. A mere idea is a starting point where you are free to examine things with a decidedly nonscientific frame of mind. You can think philosophically and make assumptions, suppositions, and all manner of mental gymnastics that are repugnant to science. Nevertheless, when the idea is developed, and you must move on, it’s time to start thinking like a scientist. Your attention becomes narrowly focused on empirical observation.

The research question will generally be loftier than a formal hypothesis, phrased in terms of conceptual definitions rather than the specific operational definitions that are the hallmarks of a good formal hypothesis.

Research Hypotheses

In many scientific research projects, the development of a testable hypothesis serves as a critical foundation for the rest of a study. Research design considerations, the population to be studied, and the methods used to collect and analyze data are all heavily influenced by the hypothesis. In essence, a research hypothesis is a statement of the researcher’s prediction. A good research hypothesis will be stated in terms of real-world outcomes rather than theoretical or philosophical terms.

However, in fields like historical research and qualitative political science studies, the focus may shift from testable hypotheses to more nuanced research questions or objectives. While these studies may not offer quantifiable predictions, they aim to explore context, causality, or complex dynamics in depth. These types of research still benefit from rigorous design, methodological consideration, and data analysis. They often employ research questions that guide the inquiry and are designed to enhance our understanding of the phenomenon in its broader context. Note that not all studies will have a formal hypothesis. Exploratory studies and descriptive studies are often conducted when so little is known about the research area that an intelligent hypothesis cannot be formulated.

If you need to get started on developing your hypothesis before you get to Section 3 of this text, my worksheet and the video below will explain what you need to know to develop an experimental hypothesis:

Research Purposes

You may encounter research ideas that do not lend themselves to formal hypotheses. You may not be interested in examining relationships between variables, such as in qualitative research projects, or you may find that there is insufficient information to formulate a specific hypothesis. If this is the case, you should formulate a statement of your research purpose (sometimes called a research objective). In short, use a statement of purpose in the following situations:

- You want to describe a group without describing relationships among variables

- When there is not enough information in the literature to support a formal hypothesis

Null Hypotheses

In statistics, the research hypothesis is known as the alternative hypothesis. “The alternative to what?” you ask. The alternative to the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the exact opposite of your research or alternative hypothesis—A statement that no relationship exists between your variables of interest. It is a negation of your research hypothesis. If your research hypothesis is true, the null must be false. If your null hypothesis is true, then your research hypothesis is false. This may all seem very silly, but it will take on added importance in later chapters when we discuss null hypothesis significance testing.

Research Designs

So far, this text as considered the variations and issues surrounding the specification of the research questions. Fundamentally, science is about asking questions and then answering those questions. The way that the researcher proceeds from the initial research question to the answers to those questions is known as the research design. The intermediate steps that take the researcher from problem to conclusions about the problem may be relatively simple, or very complex. Along the way, the researcher must decide what data is relevant, how to collect the data, and how to analyze the data once it is collected. Much of the rest of this book is dedicated to dealing with those intermediate steps.

Historical and Qualitative Research

It’s essential to recognize that not all research approaches lend themselves to the formulation of quantitative hypotheses, especially in fields like historical research and qualitative political science studies. These areas often focus more on understanding context, processes, and narratives rather than testing specific, quantifiable predictions.

Historical Research

In historical research, you may aim to analyze patterns, explore causal mechanisms, or offer interpretive insights into past events. While you might not have a testable hypothesis, you could still articulate a research problem and an analytical framework. In this case, the research “hypothesis” could be better understood as a research question that explores particular aspects of history to achieve a nuanced understanding of an event, era, or phenomenon.

For example, instead of framing a hypothesis like “Economic decline increases the likelihood of revolutionary sentiment,” a historical study might ask, “How did economic conditions contribute to revolutionary sentiment in pre-revolutionary France?”

Qualitative Research in Political Science

Qualitative research in political science often looks at complex phenomena that can’t be easily quantified, such as the dynamics of political movements, the formation of identities, or the nuances of diplomacy. Here again, the research problem might not translate easily into a testable hypothesis. Instead, you may articulate your research objective as an open-ended question or a specific focus.

For instance, you might not pose a hypothesis like “Media exposure increases political polarization.” Instead, you could frame your research around questions such as “How does media exposure shape political opinions among different demographic groups?” or “In what ways does media contribute to political polarization?”

Iterative Process

Just like in more traditional, hypothesis-driven research, the research process for historical and qualitative research is also iterative. Literature review, data collection, and data interpretation are closely entangled. For example, a preliminary look at archival documents or interview transcripts might guide you back to reconsider your initial research question or might even inspire a related but entirely new line of inquiry.

Some Points to Consider

- Research Purpose Over Hypothesis: In these approaches, the emphasis often lies on a clearly articulated research purpose rather than a formal hypothesis. You’re aiming to answer “why” or “how” rather than testing a pre-defined “what.”

- Comprehensive Literature Review: This is still crucial as it informs the formulation of your research questions and helps place your research within the broader academic discourse.

- Methodological Flexibility: The qualitative and historical methods allow for a certain flexibility that can make it easier to explore a research problem from various angles, including ethical, cultural, and social perspectives.

- Open to Evolution: As with any research, your initial idea or question is likely to evolve. This is especially true in qualitative and historical research, where the complexity of your subject matter often becomes clearer as you delve deeper into your research.

In sum, the absence of a formal, testable hypothesis does not mean the absence of rigorous inquiry. By adapting the principles discussed earlier to the specific requirements and strengths of historical and qualitative research, you can undertake a meaningful exploration of complex, multi-faceted research problems.

A Note on Legal Research

Legal research is the process of identifying and retrieving information necessary to support legal decision-making. Unlike social scientific or natural scientific research, which often aims to discover new knowledge or test hypotheses, legal research is generally focused on finding existing laws, judicial precedents, and authoritative texts to answer specific legal questions. This form of research is essential for lawyers, legal scholars, and policymakers who need to interpret legislation, build cases, or understand the legal context of specific issues.

Methodologies often include analyzing case law, statutory law, administrative codes, and regulations. Legal research also involves the use of secondary sources like law reviews, legal dictionaries, and legal commentaries to gain a comprehensive understanding of the legal landscape surrounding a specific issue. While legal research may not involve hypotheses or experimental design, it does require a rigorous and systematic approach to ensure that all relevant legal texts and interpretations are considered. The aim is often to understand the nuances of the law and how they apply to a particular set of circumstances, rather than to generalize patterns across various social settings.

Modification History File Created: 07/24/2018 Last Modified: 09/07/2023

You are welcome to print a copy of pages from this Open Educational Resource (OER) book for your personal use. Please note that mass distribution, commercial use, or the creation of altered versions of the content for distribution are strictly prohibited. This permission is intended to support your individual learning needs while maintaining the integrity of the material.

This work is licensed under an Open Educational Resource-Quality Master Source (OER-QMS) License.